The SaaS apocalypse: What Happens When Software Costs Collapse to Zero

.png)

Published by

Published on

Read time

Category

Over a trillion dollars has been wiped from software stocks. Traders are calling it the SaaS apocalypse because to them, it feels like the end of Software as a Service as a business model. The sell-off is accelerating.

This episode examines why markets are panicking, why a company like Thomson Reuters can post strong earnings yet lose 20% of its valuation in a single week, and what SaaS CEOs are saying about it. We'll look at what might be broken about per-seat pricing, what Sam Altman means by saying every company is now an API company, and, most importantly, what history tells us about what happens next.

The real answer isn't in the stock market. It's in what happened when creation costs collapsed in music and photography, causing business models to break and be rebuilt. The same pattern is unfolding in SaaS.

What's happening in the market

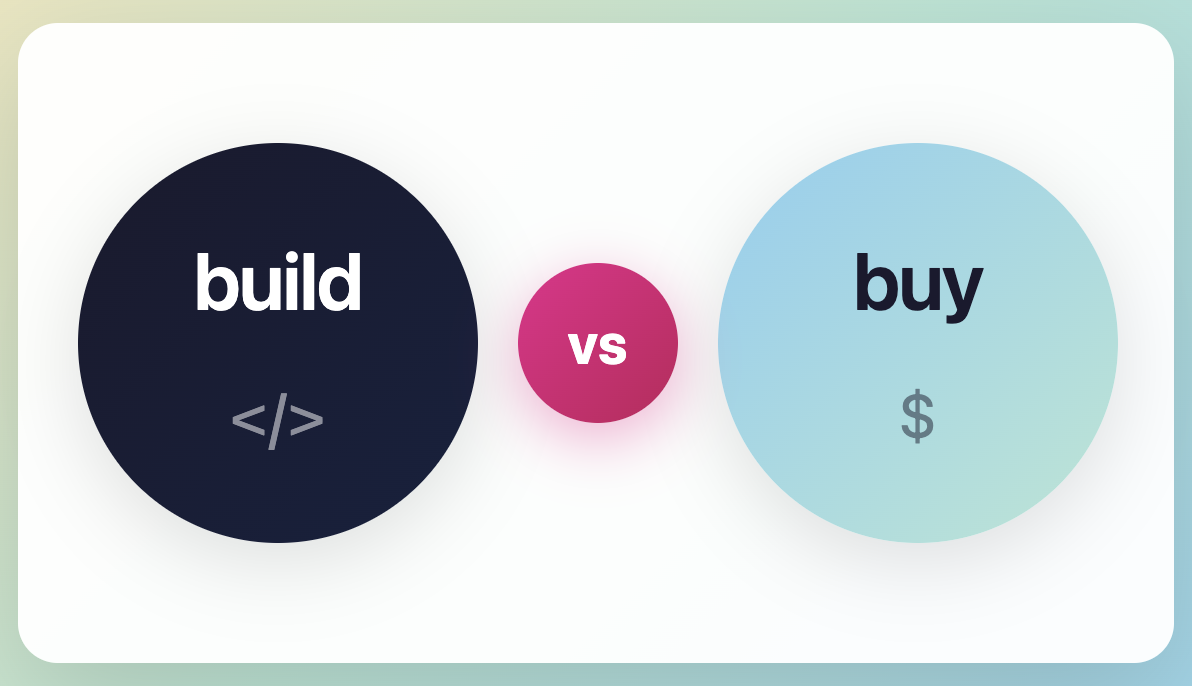

A CNBC reporter, Deirdre Bosa, with no engineering background, opened Claude Code, described a project management tool she wanted in plain English, and an hour later had a working tool plugged into her calendar and Gmail. The total cost was about $20 in compute credits.

In the same week, $830 billion in market value was lost in software stocks. Salesforce and Workday were both down more than 40% over 12 months. HubSpot fell 39%. Atlassian fell 35% in a single week. Unity lost a quarter of its value in a single day after Google released a model that can generate playable 3D worlds from natural language. Hedge funds have made over $24 billion betting against software stocks in 2026 alone, and they're increasing those positions.

The catalyst for this latest wave of panic was a legal plugin. When Anthropic released Claude Cowork plugins, it allowed the agent to follow a process simply: contract reviews, NDA triage, compliance checks. Companies in the legal sector were hit immediately: Thomson Reuters fell 18%, and LegalZoom dropped 20%. The market is watching AI companies release free or affordable tools that immediately reprice an entire software sector.

The Thomson Reuters case is particularly telling. Their stock fell 20% in a single week despite strong earnings: 7% organic revenue growth, 8% growth in adjusted EBITDA, and Big Three segment margins above 43%. The CEO stated they were seeing tangible benefits from their AI investments and planned to scale up new agentic capabilities. Strong revenue results from big businesses mean very little in the market right now. Good numbers today still leave existential questions for tomorrow.

But the more interesting question than "is software dead?" is: what happens when the cost of creation collapses to almost zero? Tech stocks are propping up global markets, so this has huge ramifications for the world economy. History gives us a clear answer, and we don't have to look far.

In 1972, the Rolling Stones spent $2 million over three years recording Exile on Main Street, with studio time costing $800 a day and major label budgets around half a million dollars. Today, an album can be recorded on a laptop for free. An AI tool like Suno can generate an entire song from a single prompt for nothing. The barrier to creating music went from millions of dollars to virtually nothing in 40 years.

The music industry didn't die, but it completely restructured. U.S. recorded music revenue peaked at about $14 billion in 1999 and collapsed to about $6.5 billion by 2009. CD sales volume and revenue lost 76%. The creation side of the business was destroyed, causing panic similar to the tech sector today.

By 2024, U.S. music revenues had recovered to $17.7 billion (the highest in history), with streaming accounting for 84% of that total. Live events, meanwhile, were generating about $23 billion in revenue. The value shifted from creation and licensing to distribution and live experiences. Spotify captured a huge amount of lost label revenue. Live experiences, which can't be digitized, thrived, with Taylor Swift's Eras Tour grossing about $2.5 billion.

Publishing followed the same pattern. The number of new titles published in the U.S. increased tenfold, from 280,000 in 2005 to 3 million by 2021, yet total revenue for the book industry hadn't moved. Amazon, which owns distribution, was the primary beneficiary.

Photography went through the same cycle. Stock images made money from ownership and licensing. When AI image generation arrived, there was panic. Shutterstock is now earning record revenue by licensing its imagery to AI companies to train their models. The value shifted to training data.

The pattern, and the Jevons Paradox

Every time the cost of creation collapses to zero, the same pattern occurs:

- The volume of that thing explodes.

- Per-unit economics collapse because the thing is no longer scarce.

- The industry restructures around whoever controls distribution and what can't be commoditized.

- The thing itself never dies, but the economic value placed on it changes.

This mirrors the Jevons Paradox, a 160-year-old economic theory. When something is made drastically cheaper and more accessible, the number of applications built with it increases. Coal becoming affordable led to an explosion of factories in the industrial era. If AI makes it ten times cheaper to create technology, people won't use a tenth as much, they'll use 100 times more.

But the Jevons Paradox also predicts what happens to many companies: more total consumption doesn't mean every existing producer gets richer. When coal got cheaper, many individual coal producers went out of business. When recording costs collapsed, more music existed, but most musicians earned less.

Ben Thompson, in his Stratechery piece on the SaaS rerating, captured the core risk: while software companies can write infinite software cheaper thanks to AI, so can every other software company. The growth story is in serious question, and the industry-wide rerating seems justified. Differentiation becomes harder when a competitor can replicate your investments. Things that used to feel less important (relationships with vendors, good marketing, strong branding) may become more important, while the technology itself becomes less important.

The counterarguments

Jensen Huang, Nvidia's CEO, called the software sell-off "the most illogical thing in the world" at the Cisco AI Summit on February 4th. His argument: if a person or an AI were to choose a tool, they'd use the best of what already exists. You'd use a screwdriver, not reinvent one. He extended this to digital tools like ServiceNow and SAP.

The SaaS CEOs who have spoken publicly are pushing a different narrative. Box CEO Aaron Levie argued that the narrative "somewhat misunderstands this idea of where companies tend to spend their resources and their time and energy." His pitch: SaaS companies will build agents on top of existing products, making subscriptions just as valuable. AI is an opportunity, not a replacement. He called it the most exciting moment in the last 20 years of technology and cloud software.

Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff said Agentforce is their fastest-growing product in history. Their moat, he argues, is that they own customer data.

There's a strong enterprise argument, too. Large organizations don't run on small apps. They run on decades of layered systems, data warehouses, custom services, and shaky integrations, constrained by compliance requirements. These businesses are risk-averse toward apps spun up by Claude in a minute.

There's also an almost logical contradiction in the panic. For the technology sector to collapse, two mutually exclusive things must be true simultaneously: AI capital expenditures are deteriorating (companies are spending huge amounts on AI with unclear profits), and AI is so effective it's making technology worthless. Both of those things can't be true at the same time.

That said, every company is at risk of being replaced by an AI-native competitor offering a better, faster, and more affordable experience. Change takes time, but companies like BlackBerry, Kodak, and Blockbuster were protected until they suddenly weren't. The timeline for change is always shorter than incumbents assume. Delayed disruption tends to arrive all at once rather than gradually.

What software becomes on the other side

Many tech companies sell based on users or "seats." If software is being bought for agents to do the work instead of humans, charging by the user is a tax on productivity. If companies slash headcount because AI lets ten people do the work of a hundred, they don't need 100 application seats. Per-user pricing faces an existential question, and the business model that's powered SaaS growth for two decades may already be breaking.

When Sam Altman was asked if software was dead, he responded: "Every company is now an API company whether they want to be or not." Interfaces are no longer what matters. What matters are the outcomes an agent can perform using the APIs companies make available. Companies will become backend systems for interfaces like ChatGPT. Value isn't in the interface, it's in the actions an agent can perform on behalf of users. APIs compete on price and functionality, not complex UI.

This also undermines Jensen Huang's screwdriver argument, because it assumes a human is picking a tool based on brand familiarity and trust. AI agents will select the optimal tool based on measurable data: cost, speed, and functionality. An agent doesn't care about UI, doesn't feel switching cost friction, and has no brand loyalty. It will switch the moment a better option shows up. If tool choice is delegated to an agent, the competitive dynamics of software change completely.

For years, a lot of SaaS products have gotten away with broken UX, persistent bugs, and missing functionality because the bar for quality was low and switching costs were high. This existential threat might finally force software companies to compete on quality, and we could see the birth of software that's genuinely good.

And there's a consistent pattern emerging that goes even further: software generated for a specific task, used once or a few times, then discarded. Software as a verb, not a noun. Instead of buying a project management tool, you describe what you need, and an agent assembles it. Instead of subscribing to an analytics dashboard, you ask a question, and the dashboard materializes. At Mindset AI, we're enabling companies to offer exactly this: a chat interface with components that an agent can pull together. Users describe the task they want to complete, and it's done.

Closing thoughts

The mistake is treating "is software dead?" as a binary question. Software isn't dead, but software as we know it might be dying.

The Jevons Paradox guarantees that when something is cheaper and easier to create, we use more of it. The software era of the last ten years (packaged products sold per user, per seat, with annual contracts, building moats on complex UI) might be over. Software has been valued at 30 to 35 times profit for the last 15 years because the market assumed big companies had 10, 20, or 30 years of market leadership. If AI contracts that horizon to five or eight years, those companies will be repriced from 30-35x profit to maybe 5, 10, or 15x.

The music industry in 2024 is bigger than it was in 1999. The software industry in 2035 will almost certainly be bigger than it is today.

The real question is whether it will be bigger in a way that today's companies can capture, or whether the value will have migrated, leaving most of them behind.

Book a demo today.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpeg)